Content warning: This story covers anorexia nervosa. If you are struggling with an eating disorder of any kind and are in need of support, please call the Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders Helpline at 1-888-375-7767.

Revised and updated: February 11, 2024

In high school, my wife, as beautiful as she has always been to me, once battled the eating disorder anorexia nervosa. She almost died. I was but a bystander, occupying a chair next to where she was to sit if only she’d overcome the disease. I was helpless; and I was, in spite of her not knowing, hopelessly in love with her.

While I daydreamed about her in my mind, how I’d get up the nerve to talk to her, to have her notice me the coming school year, all she wanted was to be invisible to everyone. In the summer before our tenth grade year, she began refusing to eat. In only a few short months, her weight plummeted more than forty-five pounds to less than eighty.

As I played basketball with my friends and snacked on a shared bag of Doritos between games, my wife undertook jumping jacks in the shower as a way to purge any calories she’d consumed earlier in the day. There were no whispers flying about that summer that reached my ears seven miles down the road in a neighboring town. I was oblivious to the transformation taking place within her mentally and physically.

Through our friendship and then our marriage, I learned from her there’s far more to anorexia hiding below the surface.

This is a story of my naïveté and ignorance. A story of a then fourteen year old boy’s high school crush. Of my wife’s struggle to be alive, to feel alive, and to stay alive. It is shared with permission and input from my wife Allison who provided additional context.

Tenth grade — 1996. Mrs. Agee’s computer class. A notecard with your name sat propped on the F-keys of the keyboard signaling your assigned seat next to me. Upon seeing your name, I tried to hide the elation that swept over me so it wasn’t visibly written on my face when you appeared.

Play it cool is the phrase.

“Hey, that’s funny,” I would say as you removed the chair from under the table to sit. “You got stuck sitting beside me again.”

The previous year in ninth grade was only the second time we’d ever had a class together: Ms. Hybl’s science class. Back table, left: you and me. Pre-assigned because of where our last names fell in the alphabet. I didn’t know you well then. I knew of you, of course. Like every boy in middle school, I thought you were beautiful. Beyond beautiful.

You were smart, too. The local newspaper confirmed as much at the end of each grading period when the honor roll was published: straight As every semester. Your life seemed to align perfectly with the stars. You had it all under control unlike me. My grades began plummeting as soon as Algebra II introduced itself into my life.

Somehow, during our entire stay in middle school, and despite our rural upbringing, we managed to have but a single class together: eighth grade art, in which you sat what felt like on the other side of the globe from me. I knew from your final project, which blew the rest of our projects out of the water, you weren’t simply beautiful and smart, you were artistic, too — your grandmother, once a painter before her eyesight was taken, who studied at the Art Institute of Chicago.

I’m not sure I ever spoke a single word to you in art that year. It would take high school for our paths to cross more frequently, and even then, it was minimal aside from Ms. Hybl’s class. But the universe had granted me another year to impress upon you.

One by one kids entered the door of Mrs. Agee’s classroom and took their seats. The clock ticked on the wall. The second hand inched forward. The bell rang and Mrs. Agee shut the door.

The seat beside me remained empty. The seat where you were to sit. I kept waiting for the door to open behind Mrs. Agee and for you to appear. When you searched the room for your seat, I was going to make eye contact with you and point toward the seat next to me. I’d watch you smile and hurry over. You’ve always had a beautiful smile.

The clock’s minute hand advanced, then the bell rang again. Class was dismissed. A feeling of sadness washed over me as I put on my backpack and pushed in my chair. I looked at the keyboard where your name card rested upright on the F-keys. I’d have to wait two more days to try my prepared line on you that I was going to pretend was entirely spontaneous. There was nothing spontaneous about it.

I didn’t know what you were going through.

“She’s lost a lot of weight,” I heard someone say at a lunch table near mine. “Like so much she could die.”

We had a jukebox in our school cafeteria, which I found odd back then and even more so now that I’m older. My buddy Dustin put a couple of quarters in the jukebox and played Skatman John. Before the Rick Roll became a thing, my friends and I would skat our entire cafeteria during lunch. It was a daily tradition. We used to drive everyone crazy playing Skatman over and over during lunch. That, and “Girl on LSD” by Tom Petty, which was always a humorous selection considering we were on school property at Randolph-Henry High School.

Everyone at our table started laughing. Normally, I would have laughed, too, but all I could hear in the back of my mind was, “Like so much she could die. Like so much she could die.”

Ski-Ba-Bop-Ba-Dop-Bop

Ski-Ba-Bop-Ba-Dop-Bop

Ski-bi dibby dib yo da dub dub

Upon the at once noticeable intro of the song, someone unamused at the table adjacent to us said, “Really?” My entire table cracked up.

“She’s down to like 80 pounds.”

“She didn’t come to class today.”

“I don’t think she’s coming.”

“I hear her parents want to hospitalize her.”

I didn’t know what you were going through.

Two days passed and Mrs. Agee’s computer class came again.

“Do you not know how beautiful you are?” I was going to say to you as you sat down beside me.

I didn’t know it had little to nothing to do with looks, that what it really was about was control: control over your own life, releasing the pressure you felt inside to be good, better, best. You seemed to have everything so under control back then.

“You’re beautiful and smart.”

You’ll never say that to her, I thought to myself. You’ll lose the courage or stumble over your words. You’ll never do that. You can barely say hi without turning red as a tomato.

“She’s lost a lot of weight . . . so much she could die,” the voice said. “So much she could die.”

I knew my inner voice was right. I’d never have the courage. So I wrote you a note. A note — that was something I could do.

I was going to give you the note on a Friday as we left class then depart immediately in a different direction. That way I could spare myself the embarrassment of your initial reaction. The weekend would then assist to ease the lingering awkwardness.

A note I never gave you — because you didn’t show that day, or that week, or that month.

Just an empty seat next to me. A notecard with your name no longer resting on the F-keys. A reminder you weren’t there.

I used to watch the door waiting for you to appear. Eventually I stopped. But occasionally, even as days passed into weeks, I would glance over my shoulder in hopes you would walk through the door as the clock’s hand ticked forward announcing the beginning of class.

“Hey, that’s funny,” I would say as you made your way over toward me. “You got stuck sitting beside me again.”

“Do you not know how beautiful you are?” I was going to say, but I didn’t understand what you were going through then. But I want you to know the beauty I saw in you was never about looks alone. The way you talked was beautiful. Your smile. Your laugh. Your personality. You were more at ease around me, even back then.

I bet I could cheer you up, I thought. You always laughed at the things I said in Ms. Hybl’s class. I bet I could cheer you up. Here, I saved you a seat.

I first wrote this essay, its original composition a vignette, in 2017 shortly before my wife and I celebrated our children’s four- and six year old birthdays and our eight year wedding anniversary. I never dated my wife in high school and she never had the faintest idea how fond of her I was. After missing her 10th grade year and while going through her recovery, she ended up dating one of my older friends who I was close with, Jeremiah. That summer I ended up falling head over heels for another girl.

I never once felt jealousy toward Jeremiah when the two began seeing one another. I was happy for him and happy for Allison. I knew she was in good hands during this time in her life. I was grateful.

In True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart, the zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh writes of the four elements of true love: lovingkindness, compassion, joy, and empathy. Of the first, he states:

To be able to give happiness and joy, you must practice deep looking directed toward the person you love. Because if you do not understand this person, you cannot love properly. Understanding is the essence of love […] Without understanding, love is an impossible thing.

Thich Nhat Hanh, True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart

When I was fourteen, I didn’t love my wife in the way I would come to love her in its truest form. I’ve always referred to my feelings then as love and have never wavered from the description. It was a youthful love, unreciprocated at the time and albeit premature, but those feelings never left me. They moved into my store consciousness until the timing was right, the seeds ready to be watered. Had I not married her a decade later, perhaps I would have relegated it to a simple crush over time.

I was, more than anything, mesmerized by her. Although I felt compassion and empathy for her in her struggle, the four elements of true love were underdeveloped. I didn’t understand her suffering; and by my lack of understanding, it was, by all definitions, impossible. I didn’t know her well enough, though I may have wanted to more than anything in the world at the time, and because of this, I did not have the ability to ease her pain.

Back then, a combination of youthful naïveté and ignorance led me to believe the eating disorder, anorexia, had its origin story in looks — specifically, that of body image and beauty. On the surface, I thought my wife had her entire life under control. She excelled in school in every subject — the top of our class. She was the picture of beauty, with every friend my age and older, unable to string together a coherent sentence in her presence. She was an amazing artist, inheriting genes from her grandmother who was an Expressionist painter. She was on the high school basketball team. She played tennis.

Until she began refusing to eat. Until she attempted to hide her downward spiral from her family even further by doing jumping jacks in the shower to shed weight she didn’t need to shed.

I was unaware of the reckoning taking place inside her. How out of control she felt her life had become. How the need to be good wasn’t good enough. How better was not best. And how severe depression, for which she wasn’t aware of at the time, had made its bed in her mind.

When I asked her why she went down the path she did as a teenager, a path that forced her exit from school, hospitalized her, and nearly killed her in the process, she first gave a one word answer (“Control”) then expanded on it:

I didn’t feel like I was in control of my life. I felt like I was under constant pressure all the time. Eating and my weight became the only thing I had direct control over. No one could control that part of me but me, so that’s what I did. It wasn’t the right thing to do but it’s what I did. I didn’t know what else to do then. It was a very dark period in my life.

In my wife’s words describing her battle with anorexia

Anorexia is categorized in the DSM as an eating disorder, and it is. But it is, first and foremost, a serious mental health condition — and a potentially deadly one at that. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD), every 52 minutes at least one person dies as a result of an eating disorder with one in five anorexia deaths by suicide. Eating disorders carry the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses.

A central tenet within Buddhism is the belief we are all interconnected (dependent origination). That we, or our experiences, exist in isolation of one another is a form of ignorance. We are connected, instead, by threads that entwine its way throughout each other and our universe.

I’ve always thought Jeremiah played a crucial role in Allison’s recovery, even if it was only a matter of keeping her from falling back into the darkness. Jeremiah was a good guy with a big heart — and one of the best friends I’ve ever had in life. He was smart and funny and I’m sure he got her out of her head by making life a little bit lighter and any burdens she had easier to carry. Without him and the support of her family, she may have died.

Had she died, this story, including what I write now, would have never been written — our two children never born. I would have never married the beautiful girl who later became my wife a month after my dad’s death from leukemia. He would have still died but instead of having a loving partner by my side, I would have been alone.

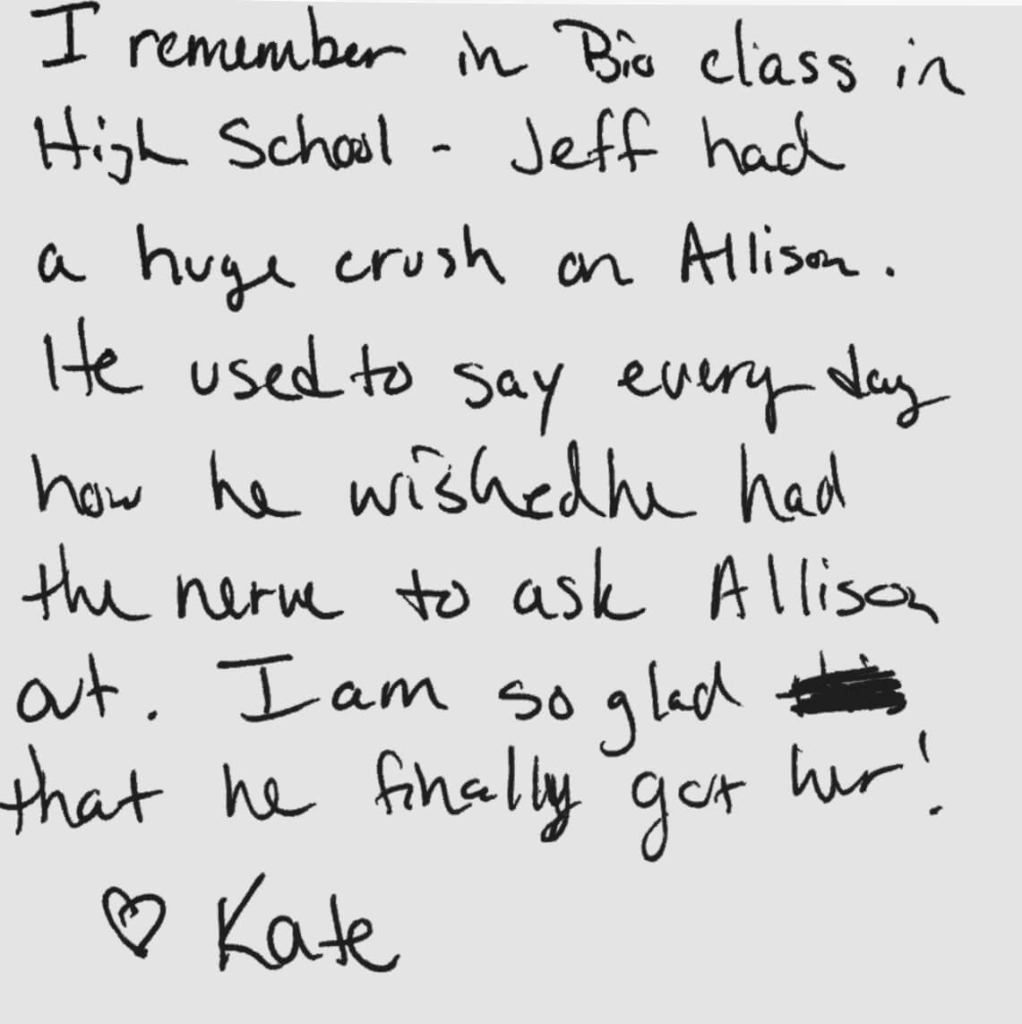

Jeremiah himself never knew of my feelings for Allison. While they dated, and even after their break-up two years later, it was a well kept secret. None of my friends knew. No one except my friend Kate. At our wedding reception in 2009, there was a table set up with a small box where friends could drop in memories they had of us, either as a couple or individually. Kate left the following note:

A few years prior, in 2006, I saw Allison for the first time since we graduated high school in 1999. We had both been invited to a mutual high school friend’s engagement party. I knew then I was going to marry her. They say you just know and I knew. I couldn’t keep my eyes off her. Aside from my friend Robbie, I’m not sure I said more than five words to anyone else at the engagement party other than Allison, who I talked to non-stop.

In 2007, Jeremiah’s life was cut short at the age of 27 by terminal brain cancer. The thread that once helped keep Allison going was gone. Allison and I had been seeing each other for only a short while. Our first kiss happened less than three weeks before when, despite her protests, I persuaded her to ride with me to a New Year’s celebration.

As the ball dropped to bring in the new year, I caught her completely off guard with a well-timed kiss. Well-timed and not figuratively alone, as in 3-2-1 HAPPY NEW YEAR! She looked like a deer in headlights when I laid one on her lips as the confetti blasted across the dance floor and sound makers went off all around us.

Had my cousin Gary not grabbed me by the shoulders and shook the life out of me, saying, “You better go kiss her. If you don’t, someone else will,” I’m not sure I would have done it. I’ve always thought of myself as a gentleman, but the reality was this: I was terrified. Kissing Allison was a plan I had for that night but it carried with it the same likelihood of me telling her she was beautiful in high school. Practicing it in one’s mind does not equate to reality.

But I kissed her and then I told her she was beautiful.

“Do you have any idea how beautiful you are to me?” I said.

It only took me ten plus years to muster up the courage — and the rest, as they say, is history.

This particular story may be of one person, my wife, but millions of Americans and those around the world are affected by an eating disorder every day. Learn more about how to spot the signs of an eating disorder or what to do if you or a loved one needs help by visiting the National Eating Disorders Association Resource Center.

Thank you for reading. I write personal essays on every day life, often with a touch of humor and nostalgia. Subscribe to get updates of new posts by email:

This blog is reader-supported. Show your support for my writing by using this link to buy me a coffee. For $5 a month or $50 a year, you help keep this blog ad-free and free for everyone to read.

Share this:

19 replies on “Do You Not Know How Beautiful You Are?”

This is one of the sweetest tributes I’ve read. Made my chin wobble a bit.

I cried when I wrote it. I’m not even exaggerating. I’ve thought about this time in my head here and there over the years, but I’ve never sat down to try to capture it in words. The tears were a-flowing this morning as I pecked away at my keyboard.

Thank you for reading.

You made my eyes leak. I’m glad your wife got better. She is indeed stunning

Truth be told, I made my own eyes leak writing this. It took me back to that time in my life. We didn’t know each other well then. We’d had the one class together, but she was such a sweet person. It was so sad to know she was going through a tough time. I remember actually being worried I would go to school one day and someone would say she had passed. Every day I always said a little prayer that she would be okay.

And you made me cry again

Extremely poignant and moving. Well done, Jeffrey!

Thanks for the kind words Rich. Means a lot coming from you.

You did me in. Beautiful. Just beautiful. My daughter was bulimic for a time and I felt so helpless as her dad. I wanted to take all her pain away but I couldn’t.

How’s your daughter now dm? I hope she’s okay. I understand it’s a lifelong struggle, and as a dad, I can certainly understand on some level how helpless you must have felt. Granted, no one ever fully understands a situation until they are in it.

I love the way you write about real stuff. The feelings you share are so beautiful. I too have struggled in this area of eating disorders and body image, and many of the things you write about… For you to share such deep and personal things from your own life’s story is truly a gift to others. Such encouragement. I’m always so excited when I have an email telling me you have a new post. Even the titles draw me in. Thank you Jeff.

Thanks for the kind words Colleen. I’ve learned more intimately about the underlying causes of eating disorders through my wife, and how it can be very different for every one. The general perception, and it’s the one I and most everyone I knew had when I was in high school, was that it was just about looks and body image. While she does indeed have body dysmorphia, her particular story goes far deeper than that. For her it was a way to “control” certain parts of herself that she didn’t feel were under her control—that an eating disorder is not solely an eating or weight issue. It’s the result, not the cause. The causes are certain mental perceptions of oneself. She’s been open to an “interview” on the topic since we started dating. I told her how helpful her story would be to others.

Jeff, reading this post reminded me of God’s faithfulness, especially in times of despair. He surely answered our prayers, and by His infinite grace, her life was not only spared, but is flourishing. Beautifully written.

Thanks for reading Pam. I know this was a tough time but I am glad everything turned out okay.

Beautiful, Jeff. As always.

Thanks Emily. I’ve wanted to write on this topic for a while because of its importance.

Jeff, what compassionate words and feelings you have shared. I remember those days well myself, as I was missing Allison’s mom, Pam, as my teaching partner and dear friend while she stayed with Allison. Those were anxious days for me as I feared for both of them. I don’t recall that we ever talked about it as teacher/student, which is sad as we could have helped each other. I am so glad that you are now able to shed light on anorexia for others. Thank you, and bless Allison, your beautiful children, and you.

Mrs. Agee

Thank you for stopping by and sharing your thoughts Mrs. Agee. I’m sure Pam missed you as well. I’ve learned a great deal about anorexia and eating disorders from being married to Allison.

This is beautiful… When one understands someone else’s struggle it’s amazing… But when one is so young to be so compassionate… Beyond amazing.

Thanks for reading, Faith, and for the kind words. I apologize for my delay in replying back. I didn’t receive a notification about this comment for whatever reason. Looking back on this time all those years ago gave it a new perspective for me and what my wife was going through at the time, unbeknownst really to most all of us, even though it was right there before our eyes.