Before you read this, read:

A note about this scene (“The Seizure”)

I said this in the introduction, which you can read here, but to repeat it again: I’m not an accountant. That’s a truer statement if ever there was one. And because I’m not an accountant, I wasn’t with Jeremiah when he had the initial seizure I’m about to describe. When I set down to write this scene nearly eighteen years ago, I drew upon the only other experience I had in seeing someone seize.

When I was in sixth grade in Ms. Bates’ class at Central Middle School in Charlotte Court House, Virginia, I had a classmate named Priscilla.* It wasn’t uncommon for Priscilla to have a seizure while in class. Another of my classmates, Keith Hatcher, always seemed to be the first on the floor to help her. He’d prop Priscilla up and keep her from banging her head on any of the desks or from biting into her tongue.

Occasionally, out of the blue, I think of this time in sixth grade and how heroic Keith was despite being so young — as young as the rest of us who stood by perplexed and frozen, not knowing what to do.

When I sent Jeremiah the story when his cancer returned in July 2006, I prefaced my letter to him by saying that I knew that this scene, in particular, may not be accurate, that I had written it based on my experience in seeing Priscilla have a seizure all those years ago in sixth grade. Jeremiah’s depiction in this scene was largely a mirror image of how Priscilla acted when a seizure came on.

Jeremiah responded in a very Jeremiah way, by saying it was okay, that he didn’t care, and to “leave it in.” He went on to say jokingly that he had no idea what happened anyway because he had blacked out.

*Sadly, Priscilla was later diagnosed with and died from a brain tumor.

JEREMIAH STARTED THE DAY like any other: a pen in one hand, a calculator in the other. Following his graduation with a degree in Business Administration from James Madison University, Jeremiah landed a job with an accounting firm based out of Charlottesville. On this day, he was busy auditing books for the local school system in Rustburg, when, interrupting his precious life, the violent shaking of his body began. He was on the phone when it started. His eyes rolled back in his head showing only the white of his sclera as his pupils focused upward toward the Heavens.

His muscles began contracting.

He could not speak.

He could not scream for help or even tell the person on the other line of the phone what was happening.

His fingers stiffened and the phone hit the ground. Jeremiah followed banging his head against the desk on the way down.

My friend, the guy I grew up with who had lived for so many years across the street from me, was having a seizure.

Within a matter of seconds, one of his co-workers walked in and saw him lying on the floor moving around as if a fish out of water. She quickly dialed 911 and the ambulance responded and was soon on their way. The seizure had finally stopped and while Jeremiah sat there in a chair drinking a glass of water waiting to be taken to the hospital, he spat out blood into an empty cup from where he had bitten the inside of his mouth and tongue minutes before.

He was scared because nothing like this had ever happened to him before and embarrassed because he had urinated his pants when the seizure began. He had lost complete control of his bodily functions and knew nothing of what had happened because he had blacked out when it all commenced.

The EMT workers walked in, checked his eyes with a small flashlight, and grasped for his wrist to check his pulse. He was still tense as they began asking questions trying to figure out more of what had just happened. Jeremiah did not remember any of it. They pulled out a stretcher to carry him to the ambulance.

Instead of being carried, Jeremiah insisted he could walk to the rescue squad without any assistance from anyone. The red lights went on and the driver hit the gas as the sirens howled penetrating volumes on its way to Lynchburg General.

Jeremiah’s mom, Mary Ann, had been notified and drove to the Emergency Room at Lynchburg General, where she awaited her now twenty four year old son, who had not lived at home in nearly six years.

Then, shortly after his arrival at the ER, another grand mal seizure; this time in front of his already petrified mother, who could do nothing but watch. This seizure was worse than the last.

Jeremiah’s dad arrives. His brother Josh. Robbie. Jeremiah’s co-workers. Pastor Collins. Diane Tuck.

“You asked what I remember about this period. I could not stop the tears. Every time someone else came to see us that day, the tears flowed.”

Jeremiah has a CT scan done late that afternoon and is told he has a brain tumor. The doctors at Lynchburg General Hospital plan for surgery on Friday; but after another CT scan, the head doctor realizes it is not something he can handle and refers him to the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville.

My phone rings.

“Jeremiah is in the hospital.”

“Hospital? Is everything …”

His skin is a pasty color white. A bruise on his forehead and cheekbone accents the color purple. You can tell he is out of it when you speak to him and the drugs the doctors have given him to quiet the seizures have done everything but knock him completely out.

His voice is subdued, splintered. The words that find their way off his lips establish their foundation in fragmented fissures like broken glass and displaced memories. His eyelids are heavy, but he forces them open long enough between intervals to let you know he is paying attention to what you are saying when it is really hard to think of anything to say at all.

Frozen forms never familiar with disquiet with one another stand on as awkward silence begs to speak. We look down at our friend lying in his bed covered in crisp, white linen sheets with an IV bag suspended in the air on one side and machines performing foreign operations and making unfamiliar noises on the other; and something speaks to us and we know this place, this hospital, this room, this circumstance and situation, is not quite right and its magnitude presents more to reality than just a seizure. Something in us all has forever changed.

Then Jeremiah starts talking about The Terminator.

“Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines. It just came out.”

“We’re going to go see it as soon as they let him out of here,” Jeremiah’s dad, Johnnie, says.

A sense of normalcy returns. Jeremiah’s tired eyes light up at the mere discussion of a machine which travels back in time to protect a man and woman from an advanced robotic assassin known as T-X played by Kristanna Loken.

I take an elevator down from the hospital to the parking lot. The elevator stops on one of the levels. The door dings. Opens. In walks a girl I used to date from Appomattox named Brooke. She’s wearing blue scrubs. I’m not sure if she’s a nurse or is just helping out at the hospital.

“How are you?” she asks.

I return home to Phenix. Find seclusion in my room. My thoughts begin to race a mile a minute. I try to wrap my brain around what is happening. I make a hasty retreat from the comfort of my home, spring down the steps, and out the front door heading toward the basketball court.

I turn on the radio in my car. 1980s new wave. A-ha. Take on me. Lay back in the seat. Close my eyes. Try to drown out my thoughts. Instead, tears. Can’t sit still. Start blubbering alone in my car. Look in the back seat. See my old green notebook and pen. 11:30 p.m.

Every event of my life and every memory conceived that I bore with my friends in childhood, I start to drain from within myself to recollect everything we had been through: from the time we were four, five, and six years old until the scattered weekends we had all spent together once everyone had went off to college years ago.

I glance down at the court. A lanky figure in blue jeans and a light gray t-shirt appears. He looks to be 11 years old. Has what can only be characterized as MacGyver hair. Even has the light brown leather jacket strewn at halfcourt. He flips the ball up in a counterclockwise spin, catches it with two hands, bounces it before another boy, age 9.

I DON’T WANT ANYBODY TO PITY ME! I’M FINE! I’M TIRED OF PEOPLE PITYING ME.

There’s an airplane in the sky. Its blinking lights pulse in the dark of the night like a star being snubbed out. Sometimes when I see an airplane flying high above, I think of you staring down at us tiny ants below.

“I’m going to be a pilot one day.”

“He only went flying once. One of the teachers at the middle school knew someone, so we went to the Farmville airport (I didn’t even know they had an airport until then), and we went out and flew over Phenix. He loved it, but that was the only time when he was a kid.”

“Is there anything you remember? I’ve never seen two people so good a friends as you two in my life.”

“I don’t remember much of anything about that time anymore. It’s like it’s locked inside of me. I just don’t remember anything. Not much. Not anymore. I don’t even know if I can.”

diagnosis noun

di·ag·no·sis

- a: the art or act of identifying a disease from its signs and symptoms

b: the decision reached by diagnosis - a: investigation or analysis of the cause or nature of a condition, situation, or problem

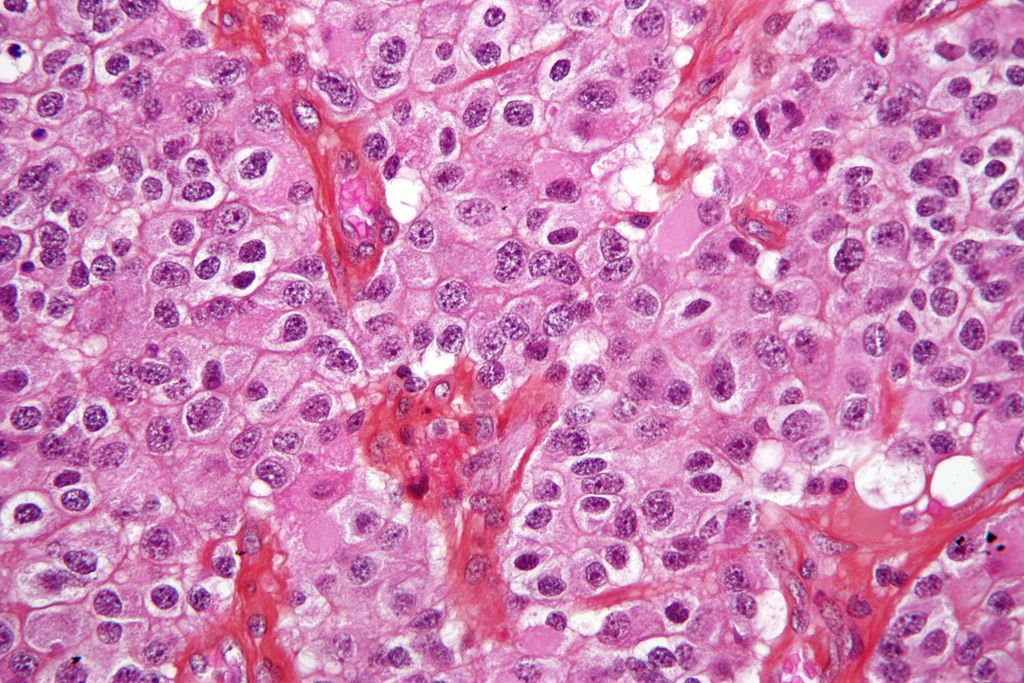

The biopsy at UVA Medical Center in Charlottesville reveals an oligodendroglioma brain tumor.

Ten year survival rate.

Jeremiah is 24 years old.

24+10=34.

As 10, 11, and 12 year olds, we used to whip up on all the 30 year olds that would come to the court and play basketball.

“One day we’ll be the 30 year olds.”

Bonnie Lawhorne, a family relative of mine and nurse in Lynchburg, tells Mary Ann to look into Duke University Medical Center. Jeremiah travels to Durham for a second opinion.

August 22, 2003

Surgery at Duke.

Another biopsy.

Anaplastic oligodendroglioma.

Five year survival rate.

24+10-5=29.

A darker haired boy, a little taller than the rest, moves toward the wing. His little brother surveys his movements.

“Switch,” the youngest says.

“It doesn’t matter,” the 11 year old boy says.

“Stop kneeing me. Every time you go for a layup, you lead with your knee.”

“I’m just doing a layup. What do you want me to do?”

“Not lead with your knee. I’m going to punch you in your face if you hit me in the stomach with your knee again.”

“How am I supposed to do a layup without my knee going up in the air? That’s how you do a layup. That’s textbook layup.”

“Switch. Y’all stop guarding each other and just play.”

“I’m going to punch you in the face.”

“I said, switch.”

“Then I’m going to punch you back.”

“See what happens if you punch me back.”

“See what happens if you punch me in the first place. I’m not scared of you.”

“You better be.”

“Will y’all stop arguing and play basketball for crying out loud? Check ball.”

You just read an excerpt from When the Lights Go Out at 10:16. A story of a 1980s/1990s childhood growing up in small town America. A story of life and friendship in the face of terminal cancer.