Before you read this, read: Creature from the Black Lagoon

WHICH BRINGS me to the cyst.

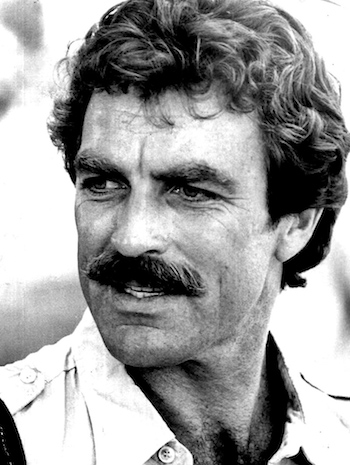

Robbie had a cyst on his upper arm between the deltoid and biceps region. It looked as if a giant worm had dug its burrow into and underneath his skin. Robbie’s scar was the epitome of cool, the archetype, the embodiment, the essence, and all other related synonyms. It was Tom Selleck’s mustache on Magnum P.I. MacGyver’s Swiss Army knife. Pee-wee Herman’s, ah, nevermind. We won’t go there. I was going to say big red bike for the record.

And damn it, I wanted one. So, one day, after a return trip from the hospital, in which I was in need of stitches on my left elbow from breaking out a window in a shed I wasn’t supposed to be in, I had accomplished my feat; and, quite frankly, was rather proud of myself.

Finally. My own cool scar. Just like Robbie. Sure, I ended up with a staph infection as always, but hey, nothing a little antibiotic ointment couldn’t take care of.

Here’s how it happened.

One day, as only fate would have it, I was inside the Gilliam shed wasting time away. I wasn’t causing any trouble or wrecking the place as some in the neighborhood would grow to think in later years, their suspicions of our mischief an ever-growing sign of their idleness. We never did that. Okay, we only did it once. The time I’m getting ready to tell you about.

The Gilliam shed was sacred ground, hallowed to us as if a church’s sanctuary. We simply sat and talked as we always did.

Of course, except this time. Yes, yes. Contradictions, I know. But bear with me. I panicked.

Panic noun

pan·ic

/ˈpanik/

a: sudden uncontrollable fear or anxiety, often causing wildly unthinking behavior.

b: a sudden unreasoning terror often accompanied by mass flight.

To continue…

My scrawny behind rested atop the wooden table toward the back of the Gilliam shed. Its wooden structure was smeared with paint and a lackluster finish. A vice grip sat firmly bolted to it along the side.

The weather on this particular day disallowed itself from having any guise or form of permanence. It would rain for a bit. Then it would stop. Minutes later, the clouds, seemingly still undecided, became resolute with their new decision, and chose to leave a light mist dancing in the air.

The humidity was almost unbearable. My shirt was weighted down by rain, yet the sweat poured from my forehead into my eyes and tasted of salt. I licked my lips and ran my tongue across them. The taste was bitter.

The Gilliam shed was a common hangout spot for many, if not all of us, during those days. It provided shelter and warmth during unseasonably horrid weather when most kids in other towns opted to stay indoors; but not us Phenix boys. More so, it aided and abetted our footprints. The Gilliam shed served in secluding us from our parents when they came calling for things like dinner and chores and homework, and from each other when need be.

The tin roof atop the shed was partially peeled back like a sardine can. Its insides stripped of life laden with rust and abandon. The aroma was unpleasant and musty; but our youthful lungs bathed in its wondrous odor regardless. Mildew painted any material, wood or otherwise, that lay exposed to the weather.

The cylindrical, vertically plastered hives of dirt daubers covered the cinder block structure’s interior reminding us that, no matter how empty the shed may have felt at times, we were not the sole proprietors of this refuge. The daubers’ songs of aggravation were heard in our ears.

Nevertheless, as I found myself undaunted, without a worry in the world inside the shed, Kevin and his friend Matthew, also known as Tater, accompanied me walking in through the back door leaping over the large cardboard box of nails that had been soaked in rain water causing them to rust. The stream of rust ran from the box and stained the concrete floor underneath like dried blood. Larry Gilliam, to our luck, also decided to pay the shed a visit.

As logical thinking children fully equipped with rhyme and reason and an ever-growing public school education, little old me being the oldest, I did what any child would do.

I panicked.

I thought about how my parents, particularly my dad, was going to give me the I’m really disappointed in you, I know you know better look.

You know the look.

The face of silence that speaks louder than any words could ever hope to achieve, that makes you feel ten times worse than any simple or complex sentence spoken, one with at least one main clause and subordinate clause, or without.

Yeah, that look.

With that image of my dad’s face fresh firmly planted in my mind’s eye, I devised a plan.

But first, I panicked again.

I knew, as did Kevin and Tater, that if we chose the back door as our egress, it would take much too long to lift the heavy, wet box of nails from the base of the door and we would be seen, caught halfway through our movement.

There was a broken window near the back that was an option quickly canceled because its panes were too small in size for anyone to climb out; and the rusted antique car just below the window offered its own obstacles (and potential need for a tetanus shot). Thus, the only other choice we had was the front door; but with this, we would walk directly into Larry Gilliam. Hence, there was only one way out: the far-side window.

The Gilliam shed was archaic, crumbling with the perils of years past. It was old school; and not old school like an MC Hammer cassette tape or a Pop Swatch watch. This childhood castle was constructed before windows were designed to open and shut with ease like today’s models; thus, when one wanted to garner fresh air in their chest cavity from a gentle, wandering breeze at the time this shed was built, the individual, man or woman, adult or child, sat upright in his or her seat, and physically walked to the door and then continued outside.

Consequently, before noticing this about the windows, that it bared all the trademarks of nineteenth, or at best, early twentieth century architectural design, I reached for the lock on the window to open it.

I looked at Kevin.

There was no lock. Dumbfounded by my discovery, I asked myself what MacGyver would do.

“What would MacGyver do?” I said. And then I pulled out the Swiss Army knife my grandfather had given me, but a Swiss Army knife would not mend this predicament. And, I had no duct tape or chewing gum either.

Curse you, MacGyver! You make it look so easy on the show.

I looked at the window again. It was covered in grime and dirt, aged with idleness. Dust draped its thick glass squares. No one had placed a cloth on its transparent form in decades. I rubbed my right hand to my left elbow and without a moment’s hesitation, I did not what MacGyver would do, but what Chuck Norris would do: I forcefully rammed my exposed elbow through a terrorist’s face, I mean, through the glass window before me.

Genius idea!

My bare elbow through glass!

Why had I not thought of this earlier?

Kevin then placed his foot in my hand and stepped onto Tater’s back and exited. Blood flowed from my elbow down my forearm. A stream of life escaped, though I barely noticed in the moment.

Pain collected its memories.

Tater then leapt out of the window following.

They were free. We had done it!

Almost.

Standing ten to fifteen yards away peering from behind a tree, Kevin looked at me signaling the coast was clear for the time being.

“Come on, man. Come on! Hurry up,” he whispered. The bass and treble of his voice low, the whisper as loud as a yell through the light rain.

It was my turn.

But there was one problem I had overlooked.

I was too big to fit through the window and, therefore, was left to hide underneath the giant chalky drywall boards that sat along the center of the room as Larry entered through the front door of his falling shed.

As I held back even the slightest sound of my heavy breathing, sweat trickled down my forehead into my eyes leaving them red and burning. The water from my eyes raced down my face as if in pursuit of the blood flowing from my elbow. Drip. Drip. Drip.

I remained hidden all the while aware of Larry’s every movement, watching his legs pace back and forth, the crisp static gathering as his left pants leg touched the right, hoping, praying he would remain in his current state, completely unaware as to my being there.

Dirt daubers sung their songs of aggravation louder than ever.

And I thought of Larry’s pistol, which I knew he owned, and said a silent prayer he wasn’t carrying.

IN ONLY A few days, the two sides of retreating flesh on my left elbow, the one I had used to ram through the window, began to meet again as the scar formed.

The black stitches smiled at me with threadlike teeth.

In my estimates, the Gilliam shed scar would now be the second coolest scar in Phenix, Virginia, behind Robbie’s. I’d take it.

According to my mom, when the doctor interrogated me, asking how I had managed to make such a deep wound on my left elbow, I responded, “The window ran into my arm.”

Years later, my peers in middle school would ask me how I had gotten the scar on my elbow and why it looked like a giant worm underneath my skin. Their inquiries brought a smile to my face.

You just read an excerpt from When the Lights Go Out at 10:16. A story of a 1980’s/1990’s childhood growing up in small town America. A story of life and friendship in the face of terminal cancer.

Photo by Nico Smit on Unsplash